Rethinking research

Established practices of academic scholarship are increasingly being questioned from both within and outside the academy. Calls for multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, or transdisciplinary approaches to research (Lawrence 2015; Nicolescu 2014; Rigolot 2020; Sellberg et al. 2021; Tress, Tress, and Fry 2005) have been taken up by research councils, whose requests for proposals seek cross-disciplinary research that is “disruptive” and “transformative” (UKRI (United Kingdom Research and Innovation) 2023). Others challenge the extractive nature of contemporary research, decrying “the field” as a space where scholars use physical co-presence with the object of study to access valuable data while, simultaneously, devaluing local knowledge systems and destabilizing local social and socioecological systems (Ahmed 2012; Guasco 2022; Loboiron 2021; Tallbear 2014; Tuhiwai Smith 2021). Still others emphasize the need for research to turn away from the advancement of grand theories and instead become more directly relevant to the world outside academia, whether through providing technologies for business and policy innovations for governments or through suggesting pathways for empowerment of marginalized communities (Herrmann et al. 2023; Kramvig et al. 2023; Marabelli and Vaast 2020).

Numerous alternative research models have been suggested to address these perceived deficiencies (or injustices) of the dominant research model. Inductive grounded theory, where explanations emerge from the research (Charmaz 2008; Strauss and Corbin 1998); community-led participatory approaches, where those being researched not only provide data but frame the questions and explanations (Castleden and Sylvestre 2023; Davis and Ramírez-Andreotta 2021; Shea 2025); open-ended, iterative research design (Bentancur and Tiscornia 2024; Brewer 2013; Sawyer 2021); and creative research methods that both facilitate involvement by members of researched communities and provide a pathway for incorporation of non-academic knowledges (Parsons, Fisher, and Nalau 2016; van den Akker and Spaapen 2017) all have their advocates. Although these calls for rethinking research are distinct from each other (e.g., one should not confuse the opening of research to insights from other disciplines with the opening to insights from other knowledge systems), the critiques and methods proposed for addressing them have some overlap. For instance, Verran and Christie’s (2011) call for “generative dialogue” includes both dialogue among researchers and between researchers and those being researched, wherein the research questions, the design of research practice, and the production of output are co-produced (see also: Horvath and Carpenter 2021). Likewise, the definition of “transdisciplinarity” proposed by Tress, Tress, and Fry (2005) (unlike that proposed by Nicolescu (2014)) explicitly includes the incorporation of non-academic knowledges as well as those from a multiplicity of disciplines. Turning from research design to its practice, Bruun and Guasco (2024) propose that a reconsideration of “the field” goes hand-in-hand with a reconsideration of established research methods. All of these innovations also require revisiting the institutional context of research. A co-created project requires a long-term commitment that is challenging in relation to institutional commitments, funding structures, and the time and trust that needs to be embedded in such an ambition (Hermann et al. 2023). Such an approach is crucial if one is to conduct research based on principles of reciprocity and mutual learning.

Largely missing from these discussions about “disruptive” research, however, is how the disruption of norms, boundaries, and practices of exclusive, extractive, monodisciplinary research requires one to also disrupt the norm of the textual academic output. For most disciplines this is the journal article, where research questions and hypotheses are posed as if they had been guiding the process from the beginning (even if they actually had evolved over the course of the project, as indeed they must in the case of co-produced or open-ended research); the discussion of methodology is reduced to a description of the context and procedures underpinning data acquisition and analysis (ideally, to facilitate replication of the study); and conclusions are offered with omniscient certainty that reflects an imagined, “God’s eye” view (contra the situated perspective promoted by scholars like Haraway (1988)).

At one level, our call to diversify the products of our research resonates with that made by many others. Researchers are often admonished to “give back” to the community that facilitated their research (e.g. Journal of Research Practice 2014), or to generate “impact” through engagement with individuals (or consultants) with expertise in forms of communication that reach beyond academia, so as to influence policy makers as well as the broader public (e.g. O’Loughlin 2018). Indeed, research councils frequently require grant holders to engage in some form of “outreach” or “impact.” However, this “outreach” is typically posed as an external activity that occurs subsequent to research and in addition to “scholarly” publication of findings. As Hawkins (2021, 2) notes, with specific reference to calls for artists to collaborate on research projects, the artists participating in such “collaborative” efforts all too often find that “art practices’ relationship to research [is] seen as a form of dissemination and perhaps public engagement” rather than “research” or even “method.”

We reject this utilitarian, transactional approach to broadening outputs for two reasons. First, it reduces the artist to a tool, ignoring the fact that artists – like their non-artist counterparts, if through different means – develop research agendas, gather data, and produce output to synthesize and communicate their findings relative to established (or contested) bodies of knowledge. Secondly, and relatedly, it diverts researchers from interrogating how different ways of defining, processing, and communicating understanding could be used to re-shape what is commonly labelled as “scholarly knowledge” or “academic outputs.”

What would it mean to truly conduct research differently, not just using different methods, for different ends, across multiple disciplines and perspectives (within and beyond academia), but also producing different outputs? For one example, it is useful to turn to the Bawaka Collective, a grouping of Indigenous and settler Australians that, since 2007, “has focused on the transformative potential of Indigenous-led tourism to strengthen communities, progress self-determination and contribute towards inter-cultural understandings through the communication of Yolngu knowledge for non-Indigenous audiences” (Bawaka Collective, n.d.). The Bawaka Collective is notable not only for its longevity but for its structure of authorship. Reflecting Yolngu ideals where communities (including the land) are the holders and tellers of stories, the first author on most Bawaka publications is Bawaka Country, followed by a diversity of contributing individual Indigenous and settler authors. The “outputs” themselves, whether academic articles, popular publications geared toward non-Indigenous audiences, or material productions with knowledge transmission (e.g. from weaving workshops), are designed to translate Yolngu perspectives that decenter academic ideals of individual authorship as well as a range of associated western ontologies (Bawaka Country et al. 2015). Perhaps most radically, the Bawaka Collective has used the vessel of the academic article to opine on topics that are not typically placed within the remit of “Indigenous studies” but that, in fact, are ones where emerging legal norms can be challenged by an Indigenous perspective (e.g. their article on outer space governance (Bawaka Country et al. 2020)).

We mention this example not to suggest that we are engaging in the kind of long-term work of translation and empowerment that guides the Bawaka Collective. However, just as the Collective’s settler researchers’ experiences working across ways of knowing have led them to not just ask different questions and answer them in different ways but to produce differently, the members of the Exploring Arctic Soundscapes project have likewise realized that this project requires a different way of thinking of “output,” whether the output being produced is an academic journal article, a musical composition, or a community meeting. This way of producing output blends the sensibilities and styles of the author and the composer, the scholar and the artist, the researcher and the researched.

Thus, the writing that follows in this article – which itself is one form of “output” that sits alongside (rather than above) the project’s compositions, concerts, and community events – is not just a “God’s eye” description and assessment of the effectiveness of an experiment in how engaging sound-in-place can build bridges across disciplines and across “researcher” and “researched” communities. The writing is intended to do that. However, following Haraway’s (1997) admonition that we blend the story, the narration of the story, and the narration of the story’s production, this writing, like the parallel artistic compositions, is also part of the experiment: one of many episodes in a circular, process-based mode where the lines between research design, research practice, and research outputs – like those between researcher and researched, and between our collective and individual identities – are blurred.

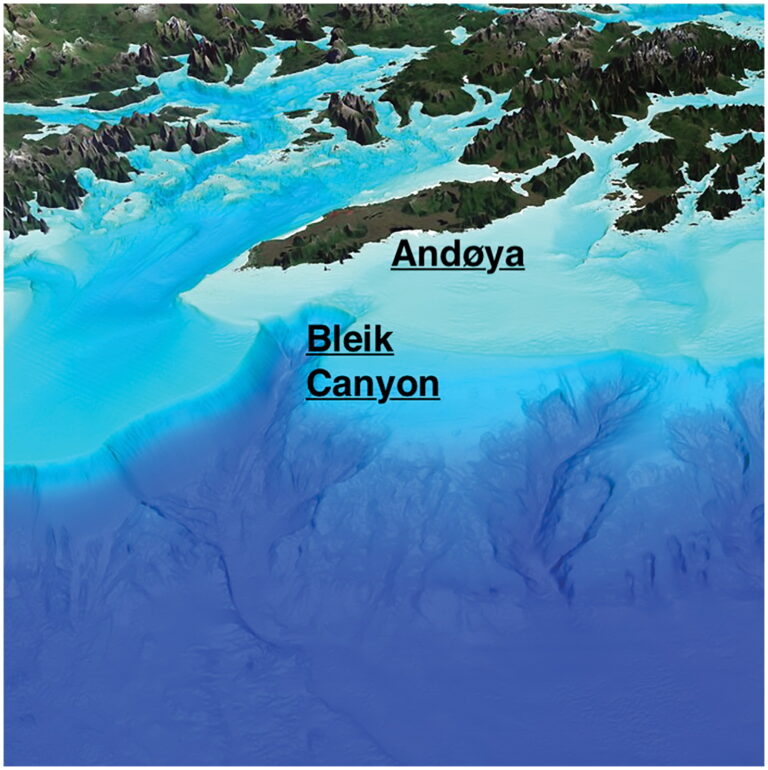

The writing that follows is also not intended to be a comprehensive, or even synthetic, accounting of the sounds heard, or inspired by, our field visits to Andøya. For this, we refer the reader to program notes from a concert in 2023 when the two main compositions resulting from the project to date – Ábifruvvá and Bleikdjupet – were performed (Musicon 2023), as well as a live recording of Ábifruvvá from that same concert (Mainly Two 2023). Rather, the focus of this article is to reflect on our method, in the sense that Law (2004) uses the word, as a complex and “messy” set of practices designed to tease out the entanglements of the socio-material world.

Given our emphasis on “output” being a process rather than a product, we also acknowledge the peer review as part of this process, not to be hidden through “corrections” but to be engaged through generative dialogue. On the initial submission of this article to GeoHumanities, one reviewer felt that we included more details than necessary and were “too anecdotal” in our discussion of how we interacted (and did not interact) with each other in the field. However, this discussion of our “fieldwork” was (and remains) intended not simply to contextualize the research but to describe the place (in the sense that Massey (1994) uses the term, as a montage of our individual and collective trajectories through space and time) that was the research “field” that we created as we interacted with each other and with various aspects of Andøya, including its sounds. Likewise, another reviewer wrote, “The point that the team sought to discard structure and questions in order to free up the creativity sure sounds like it made for an amateur field expedition.” Arguably, it was! But then the point of a dérive – perhaps the paradigmatic example of an “amateur field expedition” (Debord 1958) – is not the resulting map but the experience of making it, and the narration of that experience. Our aim, in this article, is to reproduce that experience as we also reflect on it.

That same reviewer noted: “A documentary on the activity would either be interesting or frustrating.” We’d like to think that it would be both: frustrating, in its slow wander through the intricacies of field work conducted by seven people who don’t really know each other well and don’t have a singular, unifying research question, but also interesting as a semi-linear story slowly emerges and as surprising interludes break through the underlying drone. If this article were a documentary film, it would be in the cinema verité genre, meandering through the time and space that we are creating in “the field,” with writers, artists, and composers learning from each other not just about the sounds of the research site, but about ways of listening to, interpreting, and communicating our individual and collective thoughts, textually and sonically. Or perhaps, to use a more appropriate analogy, it would be a polyphony of repeating and linearly progressing melodies complementing and informing each other, but never uniting in a single narrative.

That, in turn, takes us to the central conclusion that emerges from our reflection on the experiment: For research to be truly “disruptive” the “field” must be understood not simply as a space for data collection or hypothesis testing but as multiple spaces that are shaped by the unfolding production of ever-evolving research questions, data collection and interpretation methods, and output strategies, and these elements themselves feed into each other. This requires listening across researchers, remaining attuned to the agency of human and more-than-human others, being open and respectful to multiple modes of expression, and being attentive to knowledge hierarchies.