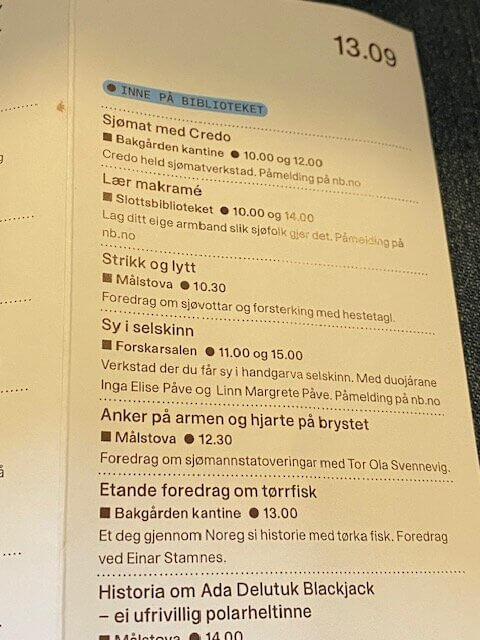

I attended a course and a mini lecture on traditional seal hunting, seal leather preparation, tanning, and sewing, alongside 15 participants of all ages. This event was organized by the Norwegian National Library in Oslo. The course was led by duodji (handcraft) lecturer Inga Elisa Påve Idivuoma from the Sámi University of Applied Sciences (Sámi Allaskuvla) and her sister, the duojár Linn Margrethe Påve. Both sisters traveled a long way from the Swedish side of Sápmi to Oslo. They grew up immersed in the Sea Sámi culture of Porsangerfjord in Finnmark, with a mother from a reindeer Sámi background. Today, both are married to Sámi reindeer herders on the Swedish side.

There is a growing interest in researching the material aspects of Sámi culture, particularly the craftsmanship and materials historically used along the coast of Northern Norway. Sealskin holds a special place as one of the most significant materials. During the course, we learned about the differences between factory-tanned and home-tanned leather. We were provided with tools, instructions, and examples to sew small keyrings. Additionally, the instructors brought samples of domestically prepared reindeer skin, allowing us to experience the differences between various types of leather through touch and smell.

In factory tanning, chemicals are used to treat the leather. “When we prepare at home, we only use natural willow bark, some salt, and leather oil” they explained. While we worked on sewing our first sealskin pieces, Inga delivered a lecture: “This is how I work with students when I teach. I start with them, working with my hands. Often, when you work with your hands, what you learn and hear settles much better in the brain. This has even been researched.”

Inga brought a variety of fabric pieces in traditional Gákti (Sámi clothing) colors for us to incorporate into our sealskin keyrings. “You shouldn’t hide the mistakes. That’s what shows it’s proper craftsmanship,” she said.

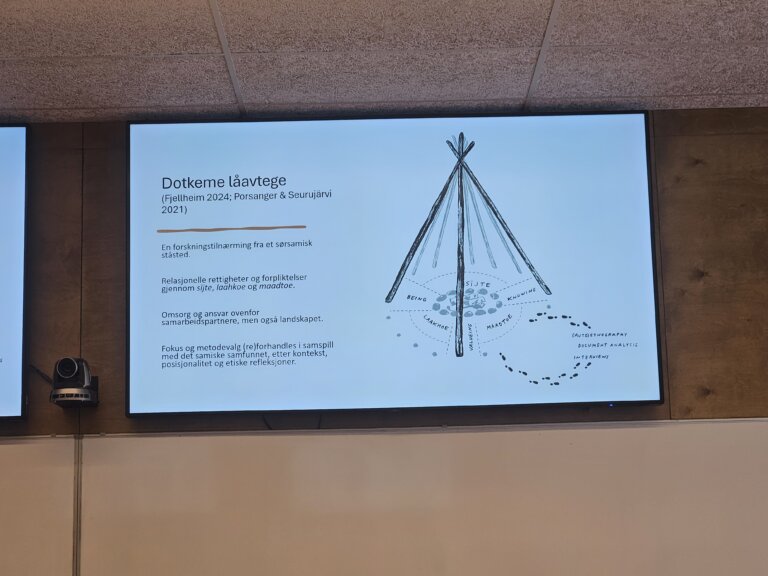

I also had the opportunity to share information about the Birgejupmi project, our work as researchers, and how Mearrasiida and Inga are part of our team. Several participants were already familiar with Birgejupmi. Unfortunately, there is still little emphasis on fully utilizing natural resources and giving back to nature what is not used. In her role at Sámi Allaskuvla, Inga collaborates with Mearrasiida on Sea Sámi matters and highlights similar revitalization projects, such as preserving the Sea Sámi boat-building tradition and collecting Sámi place names in local areas. She also discussed the project’s focus on revitalizing seals as a resource for both food and craftsmanship, emphasizing their historical importance in Sea Sámi culture.

Inga explained how the Sea Sámi region has been severely impacted by forced Norwegianization policies, which led many Sea Sámi to lose their language and culture—often without realizing it. Seals have always been a vital resource along the Norwegian coast, reflected in the landscape, culture, and traditions of seal hunting and craftsmanship. However, over the past 40–50 years, Sea Sámi self-management has been restricted by Norwegian authorities, leading to ecological imbalances. “There are too many seals now,” Inga said. “Our Greenlandic friends, who came to Porsanger to help with this revitalization project, were shocked when they saw our seals. They noticed how thin they are because they can’t find enough food. This overpopulation of seals, combined with other factors, has caused ecological catastrophes, including the disappearance of fish from the seabed.”

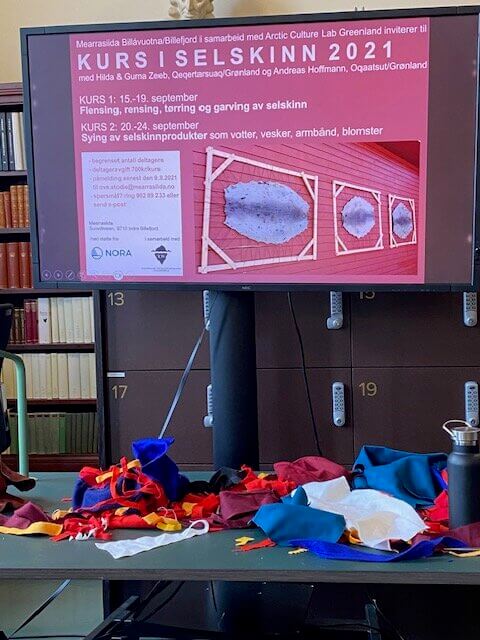

Inga continued to teach us about the different types of seals, their skins, and how they are used to make clothing, bags, shoes, and ski equipment. This tradition, though diminished, has not been entirely lost. When Mearrasiida began their revitalization project, they collaborated with Inuit experts from Greenland. An Inuit expert couple came to Porsanger to teach Sámi participants. He taught seal slaughtering and sealskin preparations, and she taught sealskin sewing and meat preparation and cooking. The second part of the course focused on sewing specialized products from sealskin. Inga emphasized the importance of utilizing the entire animal when a seal is slaughtered.

The project thus included a cooking course and how to prepare seal meat. “This is so relevant today because we need more food in the world, and we have an overpopulation of seals. It’s essential to learn how to use seals as a resource,” Inga explained. She and Linn showed a short film documenting the entire process. “We obtained three seals from the Porsangerfjord through local hunters, and the Inuit instructor knew how to slaughter them. That’s me in the picture. I have experience with reindeer slaughtering, so it wasn’t much different. But are they adults? They were so small. You can see how thin they are. In Greenland, these same seals have blubber nearly 10 cm thick, but ours only have about 2 cm. It’s terrible. I had hoped someone from the administration would attend this course so I could share this information.”

The Inuit instructors also taught the Sámi participants traditional methods of drying and stretching sealskin, techniques still used in Canada and Alaska. “We have names for all these seal pieces, which shows that this living tradition has a comprehensive terminology,” Inga said.

She displayed an old, small bridle made of seal leather: “This was placed on a reindeer’s forehead and tied behind the ears, with the face coming through here. You’d tie it at the end to guide the reindeer. This is likely cured skin, but those who moved to the coast with their reindeer often used sealskin because it’s much softer. Cured skin hardens quickly and becomes stiff.”

The course was a great success, and everyone left with their own handmade sealskin keyring.